Award-winning photographer and California native Earl Chester Waggoner’s (1916-1990) permanent artistic influence remains to be seen today through his candid, richly-colored, and emotionally resonating photographs of the Navajo people of the Monument Valley area in Arizona.

Earl’s background in sociocultural anthropology has been deposited into each vibrant photograph of his career, and his candid but sensible approach to shooting his subjects within natural regional contexts is celebrated by the fans of his work, who admire the expression of the everyday.

As part of our artist’s feature at Kachina House this month, we are showcasing Earl Waggoner’s Navajo photography by examining the themes explored through his lens in the 1950s.

The Desertscape of Arizona

After falling ill to disease, Earl Waggoner left his native Oakland, California for new opportunity in the desert climate of Prescott, Arizona. Here his interest in Navajo culture deepened. Earl eventually moved back to California to pursue a career in the financial sector, but his love for the Navajo never ceased. He often would make return trips to Arizona to remain connected to the majestic lands and its people.

Views from Hunts Mesa

While photo excavating in the presence of sunrises and sunsets, Earl Waggoner became familiarized with the natural monuments of the desert region, including God’s Eye in Hunts Mesa, which is only accessible by Navajo guide. This splendorous arch of red sandstone creates a large telescopic hole for viewers to observe the beautiful blue sky through. God’s Eye is captured in Earl’s work, and you can see this amazing structure if you look closely in the corner of his prints.

Through the Arizona Sand Dunes

Earl Waggoner loved capturing sand dune storms in the summer when he could chase the movement of the sweeping earth over the expansive Monument Valley area with his camera. On any day, Earl would come into contact with the Navajo farmers as they herded their sheep and rode their horses across the sandy terrain. When you look at his prints, you will notice imposing shadowy rock formations built into the landscape, adding haunting depth to the scene.

Snoopy Rock and the Totem Pole

Although Snoopy Rock was named after the famous Peanuts character, a greater story has been unearthed here by Earl. Snoopy Rock became a part of his photographic study when he learned that these rocks are sacred markers for the Navajo, as are the many other rock formations that make up the spiritual nesting grounds within Monument Valley where these communities traveled to. Uptown Sedona boasts the best views of these jutting totem-like structures, and visitors to the area enjoy hiking and horseback riding within the butte today.

The Navajo Lifestyle

In his photography, Earl Waggoner documented members of the Navajo nation in everyday contexts and intimate settings. Serious, close-up gazes and authentic scenes of artists, farmers, and mothers performing their most meaningful and routine duties place the observer in the middle of these moments so they are truly experiencing through picture how the Navajo people lived.

Venerating Age

The Navajo teach their young to respect those who have been on this earth for longer, stressing the importance of elderly care and respectful attitudes toward senior communities. In Native American communities, death is an inevitable part of life, and life is an opportunity to pass down wisdom, as exemplified in Earl Waggoner’s print of a Navajo grandmother. She is photographed wearing a silver “wedding balls” necklace, which is strung from her neck modestly. Many believe the necklace to be a family heirloom.

Navajo Sand Painters

Along his photographic journey Earl Waggoner encountered sand painters, who create symbolic representations of many things, including Navajo mythology, homes of Gods, and spiritual visions. Sandpaintings as ceremonial rites are used for healing practices and are usually accompanied by chanting in many instances. These paintings serve as pathways leading to transformation in members who are sick or battling illness.

Honoring Duty and Motherhood

The parental model of the Navajo nation exists in dramatic contrast to the modern-day Western model. Navajo mothers were expected to be both doting and protective while acting as the primary care givers for their children. They were also expected to nurture large families. Babies became co-dependent on their protective mothers, who carried them on their backs or in their laps everywhere they traveled in Navajo cradleboards. This Native American invention is photographed in some of Earl’s earlier work from the 1950s.

Navajo Farmers and the Three Sisters

When Monument Valley had an underground water channel running through it, Navajo farmers were able to grow corn, one of the three sisters. They stripped the corn for its pollen, to be used in ceremonies, and the cornhusk, to be used for “kneel down bread,” also known as Navajo tamales. Earl regularly photographed women in the fields stripping the corn to be prepared for cooking purposes.

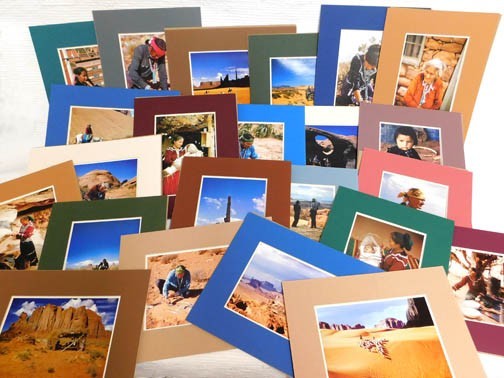

Kachina House is excited to present to our visitors the stunning matted photographs of the Navajo people and Monument Valley by Earl Waggoner, available for purchase here. If you have any questions about his work, feel free to stop in!